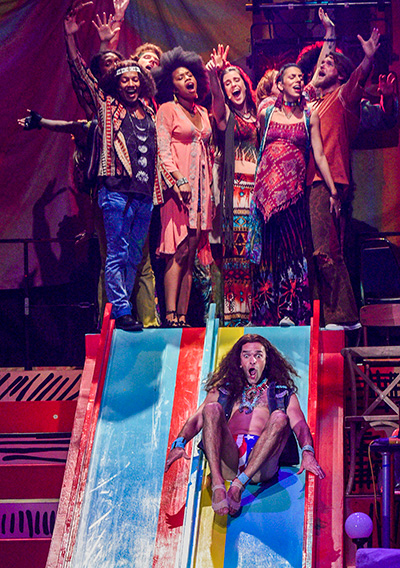

DTC’s Tribe of Hair.

Photos by Karen Almond.

Kevin Moriarty was turned on to Hair by the nuns at his Catholic elementary school. A few years ago, he directed a nudity-free version for student actors at Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts, and it made the Dallas Theater Center artistic director ask himself whether the 1967 musical might still be relevant on its 50th anniversary. The answer was yes, he says, so DTC has mounted a new production under his direction, running through Oct. 22. Manuel Mendoza sat down with Moriarty to talk about why he wanted to bring Hair back and what his production looks like.

Hair, huh?

Let the sunshine in.

Besides being the 50th anniversary, why do it now? Isn’t it dated?

When you look back at 1967, you see a nation trapped in an unpopular, unwinnable war against an ideologically murky foe. You see a nation torn apart about individual identity, including race, sexuality and gender. And you see a country that has lost faith across the political spectrum in institutions — trust in the media, trust in government officials. In other words, the historical moment of 1967 suddenly sounds a lot like the current moment of 2017. And there are some really great songs.

There was a certain innocence to be lost then that we don’t have the luxury of today. As bad as things were, there seemed to be possibilities.

I think you’re right. What we discovered in the rehearsal room is that while the story, the songs, the social-political themes are instantly accessible to the actors, who are all in their 20s and weren’t alive in 1967, what is the hardest thing to tap into is the spirit of joy and optimism and hope that permeated the Summer of Love. The teenagers and young adults who were dropping out were largely doing so in an incredibly positive and hopeful vein. That they could by rejecting the values of their parents and organized society, notions of money and law, restrictions of sexual expressions and use of drugs — by rejecting that, they could usher in an age of peace and harmony.

Now we seem more trapped.

Today, when you look somewhere like Twitter, the equivalence of folks gathering in Haight-Ashbury, you find much less optimism and hope and more acrimony and dividing into our two sides, us and them. What’s striking to me about Hair and about looking at the late 1960s is seeing how much is similar and then asking ourselves, ‘Is there a place in our current national dialogue for a renewed exploration of alternative ways of living and being? Are we at the moment when we need a new generation of young folks to help lead a major reformation of American social, spiritual, political and sexual life.’ I’m not sure how our audience will respond to that question, but it’s a question that’s compelling to ask.

At the same time, the 1960s have influenced society in ways that we don’t think about, like the acceptance of alternative medicine.

The reading I grew up with in the ’80s was that the hippies became the Reagan Republicans, sold out their values and it was all for naught. I actually think when you look at the legacy of 1967, what you see is medicine and food. It’s inconceivable that a massive store like Whole Foods or Alice Waters’ movement of eating local and eating fresh could have happened without the hippies. The fact that my generation and all of the generations younger than me have never known a draft. The fact that we had an African-American president and that women have ascended to so many powerful positions. The fact that birth control is widely available and utilized by a broad cross-section of American women.

What kind of musical is Hair?

In the same way that the hippies were questioning the assumed principles of life, the musical Hair attempts to break all the rules of what a well-made play should be. What Rodgers and Hammerstein did to establish the virtues of a great musical, Hair attempts to subvert, largely doing away with the primacy of narrative as the driving force. It assaults notions of character, of time and place, and substitutes a collision of ideas and emotions and performative styles.

How is your production designed?

We took out the proscenium, the orchestra pit and the balconies, covered the walls with cardboard and tie-dyed fabric and built four seating banks that are different neighborhoods with their own character.

Describe the neighborhoods.

One of them is a lounge, and it has mattresses and couches. One is called the kitchen, and has a tile floor, and some of the audience members will be making peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and handing them out. One is called the playground, and has a massive metal slide that the audience and the actors can slide down. One area is called the garden. There are no theater chairs. Instead, we have 500 found objects: dining room chairs, beanbags, whatever we could find. So when the audience comes in 30 minutes before the show, we will launch a spontaneous Happening that will be different every night. You choose your neighborhood and might be given permanent markers and invited to draw on the walls or the floor or the stage itself.

What else will happen during the Happenings?

We’ll have face painting, tarot card readings, and that spirit will continue during the show, with moments when audience members will be put in costume and will engage in scripted dialogue with character in the play. We are trying to make the experience as immersive as possible — a fully authentic feeling of what it could’ve been like to have been in a warehouse or a park in the Summer of Love with music at the center of the room and young people exploring the possibility of a world with no limits and with peace and harmony as principles.

—MANNY MENDOZA