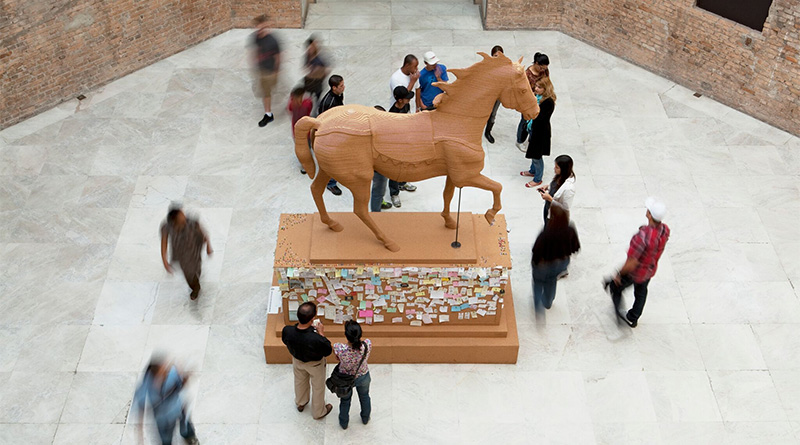

Paul Ramírez Jonas

The Commons, 2011

Cork, pushpins, and hardware

153 x 128 x 64 inches

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Nara Roesler.

Framed inkjet prints on paper, music stand, amplifier, and microphone

Dimensions variable

Work and image courtesy the artist.

Mid-career retrospectives have a way of messing with their subjects’ heads. When you’re used to always thinking about the next project, looking back on decades’ worth of work can produce as much anxiety as nostalgia.

That’s why “I have a little mental trick that I play on myself,” says Paul Ramírez Jonas, whose 25-year survey is on view through April 29-Aug. 6 at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. “I keep referring to this as ‘Dean’s show.’”

“Dean” is CAMH curator Dean Daderko, who has known Ramírez Jonas for 24 of those 25 years. Atlas, Plural, Monumental, which Daderko organized, sounds like the title of a thematic group show rather than “Paul’s show,” which is what it is, though the artist’s name is missing from the title.

That kind of self-effacement is a silent hallmark of Ramírez Jonas’s participatory brand of sculpture and social practice. It was integral to one of his breakthrough public artworks, Taylor Square, for which he mailed 5,000 keys to the Cambridge, MA, households surrounding a tiny—57 square feet, to be exact—new locked, gated park. Residents were welcome to make and give away as many copies as they liked.

“My name didn’t appear anywhere, so this work is a work of public art made for the people in this neighborhood.” Ramírez Jonas says. “Who made it isn’t important. It engages them and reminds them that when we say ‘public,’ we mean actual people. It means all of us together. Public space belongs to you.”

Top of the World (Red Ball), 1997

Latex rubber

10 x 73 (diam.) inches

Work and image courtesy of the artist.

Not all of Ramírez Jonas’s works have been quite so anonymous. In some of his early series reenacting historical inventions, he appeared in photographs or videos documenting actions, but “I was putting myself in, not as me as a special artist, but hoping that the viewer would say, ‘That could have been me. Any of us could do this.’”

That spirit animated Heavier than Air, a body of work from the early 1990s for which Ramírez Jonas faithfully replicated kite prototypes designed during the Wright Brothers era by inventors such as Alexander Graham Bell and Joseph Lecornu to explore the possibilities for aeronautical flight—with one crude, yet eerily prescient modification.

“He basically hacked an alarm clock, MacGyver-style, so that it would depress the shutter of a single-use disposable camera,” Daderko says. “This alarm clock-camera hybrid was then tied onto the tether of the kite and set, and Paul would take them out to the beach, launch them into the air, and then whenever the timer went off they’d take an image down the string of the kite, and so you see an image of Paul on the ground. Sometimes he’s like a tiny dot because the kite has flown really high; other times you see him a little bit better.”

In hindsight, it seems like a primitive drone—even more so when you hear that for the exhibition poster Ramírez Jonas used an image of Russian missiles taken by the U-2 spy plane during the Cuban missile crisis to evoke what he calls the kites’ “eye-in-the-sky implications.”

“It’s like a very innocent moment,” Ramírez Jonas says of the early 20th century, when the kite prototypes were designed. “The plane is not used for anything yet. It’s almost like a pure pursuit. There’s all these inventors in Europe and the United States thinking, ‘The time has come. We’re going to make it,’ but with no clear idea what it is going to be used for. And in less than ten years, there’s already warplanes and airmail and passenger service.”

His Truth is Marching On, 1993

Wood, wine bottles, water, mallet, and hardware

16 x 84 (diam.) inches

The Dikeou Collection, Denver, CO.

As a student, Ramírez Jonas tried grappling with history through painting, earning a master’s degree in the discipline from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1989. But at student critiques when he presented works like a canvas depicting the Battle of the Monitor and Merrimack—an 1862 naval Civil War battle, the first with ironclad ships—people only addressed formal issues, sidestepping subject matter completely. “I realized: ‘No one knows what this painting is about,’” he says.

Experiences like that led Ramírez Jonas to work in ways that ensure formal considerations “facilitate the meaning, not get in the way.”

“I think of form as good service,” he says. “If you go to a restaurant, and the service is really good, you kind of shouldn’t see it.”

His Truth is Marching On (1993), an early participatory sculpture comprised of a hanging, circular arrangement of wine bottles, has affinities with the primary forms of minimalism and the found-object tradition. But it truly comes alive when a viewer takes a provided mallet and taps the bottles, each filled with a different amount of water, in succession to play a rendition of “The Battle Hymn of The Republic.”

Or perhaps it’s a rendition of “Say Brothers, Will You Meet Us,” a tune that emerged out of the American frontier camp meetings associated with the Second Great Awakening of the early 19th century. Or of “John Brown’s Body,” a popular abolitionist song. Or of Ralph Chaplin’s 1915 labor union anthem “Solidarity Forever.” The melody for each is the same, or as Ramírez Jonas notes, it “took on different meanings. It was a vessel with an empty form.”

Ramírez Jonas, an associate professor at Hunter College, likens his role as an artist to that of a teacher helping his students make their own discoveries.

“Increasingly with the participatory work, the thing is: How do you create the parameters for people to be creative and make a contribution?” Ramírez Jonas says. “In pedagogy, that’s also true: You exert a certain amount of control. You structure the class; you structure the assignment; you put in restrictions and then open them. In a way, I see that really clearly: You need both. You need the restraint and you need the openness in order for it to work.”

—DEVON BRITT-DARBY